THE LIQUID OF HER

Ken Poyner

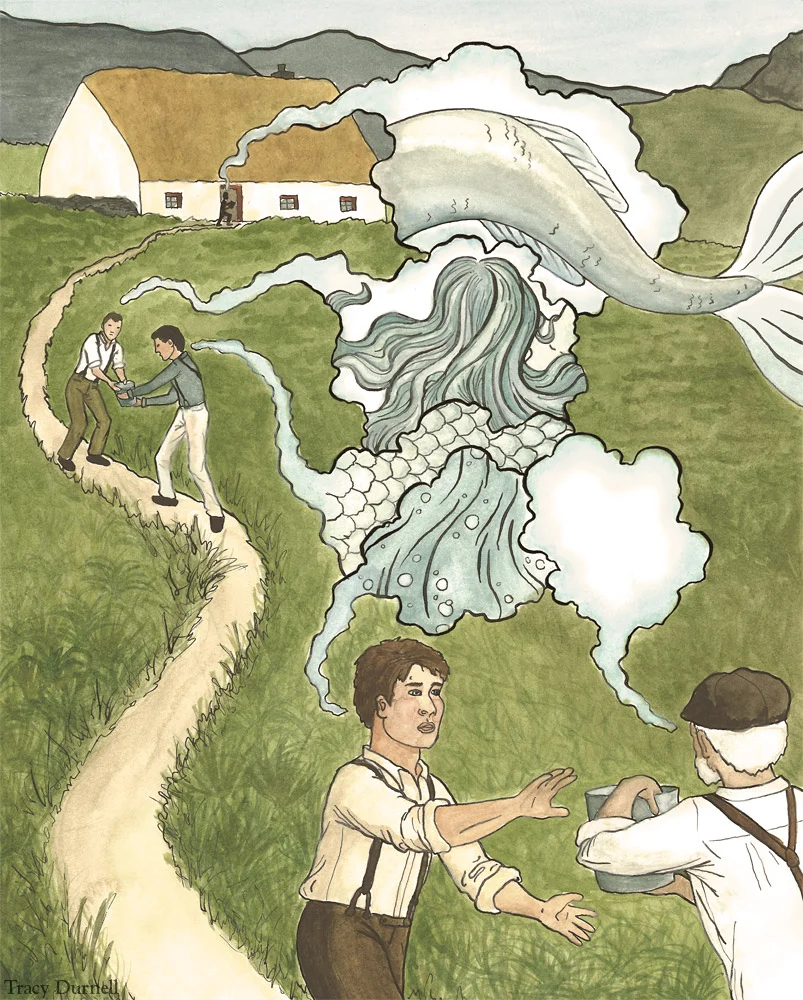

Art by Tracy Durnell

We bring up half-filled buckets of water from the river. Each man sloshes a few feet, passes the bucket to the next. There are not enough of us to line up shoulder to shoulder and pass each bucket without moving our feet, but each man stakes out his eight or nine foot run, learns the best shuffle and glide to make to keep the buckets moving. Sometimes, the steps are different heading inland than they are when, unburdened and empty handed, each man makes it back to his waiting place closer to the river.

At the last, the bucket disappears into the cabin’s open mouth and the final man of the line can hear the splash as the contents are tossed full force. And then the bucket comes back out, being passed to the nearest idle boy to be run back to the river’s edge.

We cannot keep this up for long. The same men that would build a tank are now hauling water. In any case, a tank would require planning, a theory about the size of tank needed, wood and sealant, perhaps iron constricting bands. Most of all it would take time. There is the will for a tank, but no time, no planning, no ready material. And then we would have to fill it.

The rumor has been passed more than once that she is drying out. Ever since she left the river and was claimed by the cabin, it can be inferred by anyone who has fished for his sustenance that she has been desiccating. It is inevitable. Feel how dry our air is. Even the river in its currents runs away from us. Everything about us is brittle and thin in spirit. To urinate is to make an admission of excess.

No one knows how she made it into the lonely man’s cabin. He claims to have found her there, but if what I have heard third hand about her fluke is true, I think it more likely she was dragged, someone later scuffing away the land marks. Yet finding her beached by herself in the cabin is most convenient. In imagination, the features of her growing ever larger, to drag this mermaid would soon take more than one man, and there would be conspiracy in the air.

But for the moment, I take the bucket offered me, and after two yards of slide, a half turn, three steps and a stabilizing squat, pass it like recovered laundry to the next man, who must, like me, wonder how long we can hold out. Excess water runs back towards us, both retreating from the cabin and leaping out of the buckets brutalized in our haste.

I do not want to see her dry up. I will do my best, but I wonder: why this man’s cabin, why this man, what deeper end are we serving? There are enough of us to take her back to the river. There is nothing special in holding her in the cabin.

We could wrap ourselves, a few men to each side, around her agile, buoyancy sized chest, pinch in at the waist, then cradle the scales of her hips in textile fine forearms. And two men could come behind, one on each side of the sensuous fluke: those two stepping forward, and the rest of us, shuffling crab-like side to side, down the well-worn path to the river.

Each of us first hand could then know her gasping, could gauge the liquid of her, countenance the rough of her scales. Laboring and not knowing her details sticks with us like fish bones. Her hair, if it is long and sea foam, could flow over our shoulders and whip at our thighs. Each man could inhale the eerie fresh water scent of her, imagine the salt to brine to fresh transmutation as she made her way longingly up the river. Each of us could see and smell the ripening bubbles caught in her breath.

And we would hurry, hurry down the path to the river, understanding better our mission and the limp compact of her and us and the river and the distant sea: our backs straining then with her weight and not with merely the weight of the water that sustains her.

But no. At this moment one man receives the bucket, tosses the water across her, and tells no one. What right has he? Of the rest of us: some get a glimpse, some get a sound, some get nothing but the part they are asked to play.

I say we can carry her before she stiffens like a fish in the bottom of a dry canoe. I say we can support her. I have not seen even evidence of her, but surely my arms can reach half way around her. I have the strength to be a hero in person. We can in one communal rush slip her comfortably grazed into the river, where she will frolic out a bit, and then surely turn back, with the glint of gratitude mixed in with the sea storms of the anadromous drive that brought her so far.

But here is the next bucket. Take it. Yes, you. We cannot let her dry out, we cannot let her desiccate. No matter what purposes can come out of the facts that linger with us. She, for the moment, is the best this village has going for it. Perhaps we will carry her back to the river, perhaps we will build a tank. At the moment one special man tosses water and the rest of us supply. You cannot let our hopes turn to leather.

KEN POYNER’s latest collection of short, wiry fiction, “Constant Animals”, and his latest collections of poetry—“Victims of a Failed Civics” and “The Book of Robot”—can be obtained from Barking Moose Press, at www.barkingmoosepress.com. Look for “Avenging Cartography”, flash, coming in mid-2017. He often serves as strange, bewildering eye-candy at his wife’s power lifting affairs. His poetry of late has been sunning in “Analog”, “Asimov’s”, “Poet Lore”; and his fiction has yowled in “Spank the Carp”, “Red Truck”, “Café Irreal”. www.kpoyner.com.