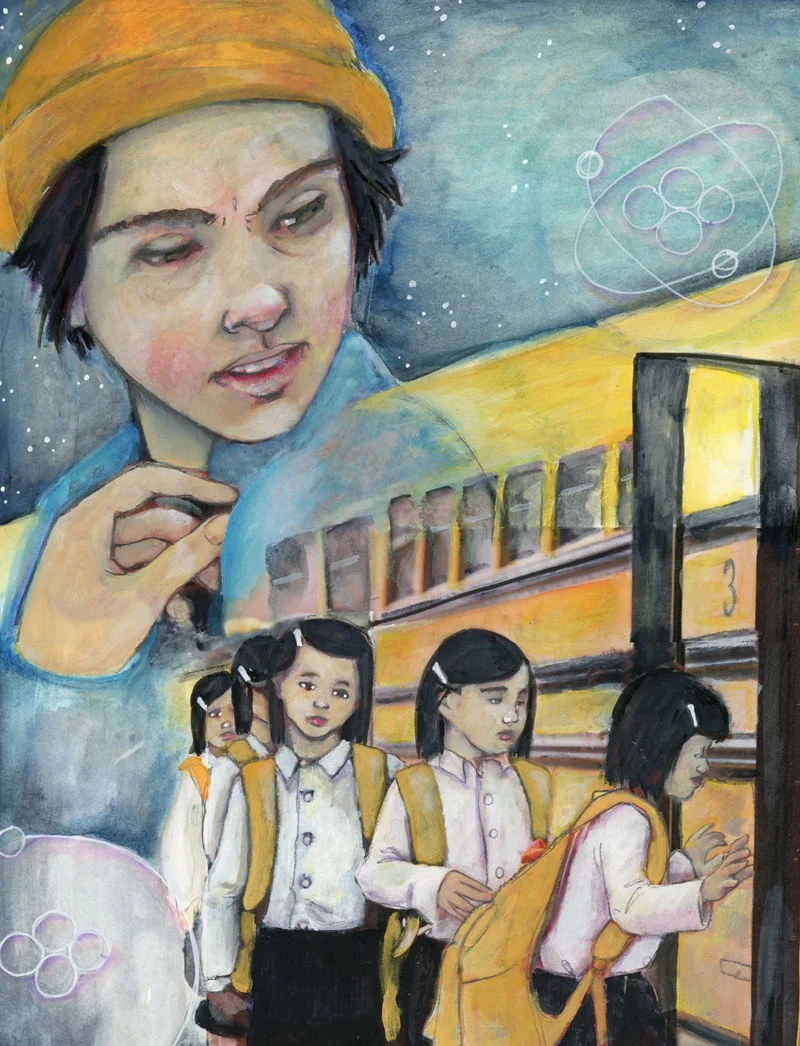

THE BARRETTE GIRLS

Sara Saab

Art by Laurie Noel

When we get to Euston Station, we help them change trains, and the barrette girls do not resist us.

Andrew says, "They told us to be gentle with them, Sunday."

For his sake I touch them gingerly and coo to reassure them. I hand around the kind of water bottle you buy at a gas station, five liters in flimsy plastic, and they drink with the desperation of suckling cubs.

Andrew asks, "Where will they all sleep?"

I reply, "It's not supposed to rain tomorrow," because he should not be so obvious in public.

The station is full of people who watch us. They look at the orange knapsacks we have put on all the girls to make them seem part of an organized tour, here to learn English or ramble in the frosted countryside. Andrew and I wear orange hats. The girls' knapsacks are a different shade of orange to our hats. Andrew was late, so we bought the knapsacks in a rush from a TK Maxx near the pick-up point.

The barrette girls do not speak on the Tube. There is no place for every one of them to sit and so they stand. Andrew shrugs and sits down. The girls, who do not sit, bump each other with their orange decoy knapsacks, unwitting. Some girls catch a bag in the face but do not react, as if a bag is just a buffet of underground air.

They've never been on the Tube before, and all the passengers can see this. They are not nervous, not bored either. Their lips are not stretched bloodless dry over set teeth. They are uncanny in their calm.

"The next stop," I say to Andrew. He stands to grasp the hand of one of them, and he singsongs come on. The train doors piston open. They all follow without a word, the mother-of-pearl barrettes a spill of mercury in the nests of their hair.

You might accuse me of loathing the barrette girls because of my inherent similarity to them. Not similarity exactly—I am old enough to have raised them—but perhaps a kind of parallel? Between how the barrette girls have suffered and how I have suffered. But even our suffering is fundamentally dissimilar.

My suffering is because of how I've been wronged.

I have been wronged many times over. Patrick wronged me when we were children; I remember the smell of cigarettes on his fourteen-year-old fingers, fingers too young yet for tobacco stains. Dascha wronged me when she fucked me even though her heart had been hollow a long time. She let me love her; she leaked my love like a cheap thing. The Barthes wronged me by casting me out when I had nowhere to go. I stood on the stoop and shouted up at the bedroom window, my fingers fixed solid to the handle of my suitcase by the icy wind, but they did not let me in.

Society has not wronged the barrette girls. They are not the kinds of things that can be wronged. No one has ever dared touch them in a way they shouldn't. No one has ever cheated on them. Evicted them. These violent verbs could strain and strain and still do not a whit of harm to the barrette girls.

Andrew is gesturing to me: come on, Sunday, unlock the padlock, let us get out of the rain. This street is made beautiful by the brass instruments workshop. The saxophones and trombones and tubas in the display dazzle me. They are crisp and wondrous as Christmas ornaments in the light of the streetlamp. Across the street, I open our padlock and our door, squeeze past Andrew and the barrette girls.

So far, Andrew has not wronged me.

Consider what you know to be a person. Consider the most solid person you know, your brother Patrick, Dascha your ex-lover, Dr Ganesh who drags you through your Mineral Sciences degree one grant, one research proposal, one data review meeting at a time. They are fully people; they are not modular, they do not come apart like a bedside lamp or a clock or a toy spaceshuttle built of blocks.

The fact that they are so very deeply people glues their parts together, makes it hard to imagine this next thing, but imagine it anyway:

Take away pieces from Patrick, Dascha, Dr Ganesh, miserly Asher Barthes and his wife. Take away a little finger first. It's still Patrick, a bit less tobacco-stained, his grip on your neck minutely softer. Patrick nonetheless. Venture inwards now, towards the so-fragile torso, and open up, and take pieces. Gape apart the ribs, take what you find beneath. The more inward, the more central, the more impossible it seems to be lifting away these segments of ones who were people, and all this blood is a curtain, for privacy, for sanctity, because without the blood it is all too obscene, to lift away lung heart gullet stomach, it should not be possible. But it is.

The barrette girls clump together on top of the overlap of sleeping bags Andrew laid out. They use each other as pillows, their configurations catlike, graceful. Each of them has taken their barrette out, let their hair hang loose as they offered the sharp, shining thing to us on upturned palms. The stacked barrettes are graceful too. The stack leans against the exposed brick wall of the dining room: a compound jeweled insect. The barrette girls do not snore, or pass wind, or mumble the names of playground crushes in their sleep.

I find Andrew in the kitchen, where he is pouring a tall glass of water with tremendous care, as if measuring out ingredients. Andrew moves like a much older person, much older than himself, much older than me. I need to remind myself that he is fifteen years my junior, and that these are his first barrette girls, and that he is scared.

The house is dark except for the incongruous lamp with the green velvet shade on the rickety kitchen counter. It casts the white cupboards in dirty seafoam. The kitchen smells like frying steak. There's no trace of food anywhere. I look out the window, see the brass instruments workshop across the street, see the wedges of shine on the great tuba in the main display.

"Do you play any instruments?" I ask Andrew.

He takes a sip in slow motion. His hands shake, his strong hands with their square palms and slender joints.

"No. The recorder. Jingle Bells on the recorder."

"I'd like to learn to play a big, heavy wind instrument," I say. I point out the window. "Just gas moving through a delicate vessel, a simple thing. But ethereal. Beautiful."

Andrew catches my crass analogy and sets his glass carefully down on marble, clink, stretches a steadying hand out beside it.

"I don't feel well, Sunday. I feel ill." He looks at me wild-eyed. His voice dips. "They said they were obvious fakes, just real enough to pass in a crowd. They're not fakes. They've got little eyelids with veins in them. They wet their lips. Their hands are warm and they hold with the exact grip of a—" Andrew flexes his free hand, "child."

"You were fine on the Tube."

"Was I? Okay." His voice cracks.

"Too loud, shh. You'll wake them up."

"Who cares, Sunday? Do they really need to sleep?"

"Handling instructions. You wouldn't store a bottle of wine on a sunlit windowsill."

Andrew moves his glass to the sink. Walks past me and up the stairs to the bedrooms in the dark. I've irked him. I suppose I wanted to, but not out of a personal vendetta. It simply feels right that we should both be that way. Irked.

Years ago. My first barrette girls. This was before I'd ever met Dascha. I was barely an adult. There were only two of them, experiments, and back then they would give them names to aid identification. Code names, yes, but still names, with the humanizing power of names. Officially, we called these two Monsoon and Typhoon. For the days that I had them, I called them Money and Ty.

I picked them up at St Pancras International. They'd been sent on the Eurostar with a minder; in their hands they each clasped a box of favors from the train. Cartoon lettering: Conductor in Training. I remember the word Training was rendered zooming along a track. The minder's name I've forgotten, even though it was the password we used in the pick-up.

To remember which girl was which I scratched an 'M' and a 'T' on respective wrists with a ballpoint pen. I talked to them the whole time. I told them my favorite bedtime story on the train to the house. My father had repeated it to Patrick and me so often I used to mouth the words falling asleep.

Money and Ty weren't interested in my story. Or anything over the next three days. Money wasn't interested when I accidentally clipped her lip with the showerhead while—contrary to protocol—bathing her that night. Fat coins of blood appeared on ceramic. The blood was red; the blood looked real. Money did not cry. What I can say with confidence is that she did not know.

And one time I heard Ty make a high-pitched sound in her throat. It froze me in place. But I don't think Ty knew either.

They were experiments.

The loathing I feel now was germinating then, silently, a disease before the first symptom shows. And when I took my barrette girls to the location and saw how they worked I understood not to name them, not to ever, ever name them, and I fed the anger. Anger is a useful curtain, like blood. Anger is separate from my own hurt.

It's the morning of the day the barrette girls must be moved to the location. I go out among the people who watch, but they do not watch me, because alone I am anonymous: a woman in a merino wool hat, a woman in a blue weatherproof jacket, a woman with short hair, a hard woman among all the hard women in London. Unwatched, I secure the street made beautiful by the brass instruments workshop. I send up drone cameras that look like cloudy marbles into the boughs of trees, and between designated trees I press my cold fingers against the warm winter softness of my belly.

Andrew has not come down from his bedroom yet. I heard the sharp in-breaths of crying when I stood at his door. My fingers hovered but did not knock.

Downstairs the barrette girls were awake. I'd handed back their barrettes in silence, but in my head was a litany of words. The words started out so harsh that my ears recoiled from the inside, assortments of four letters, one for each girl who stood before me, hands cupped. But I set my jaw and thought kinder words, words like trombone, saxophone, horn. These were not names. They were just words to ease the moment.

Dascha and I met at my first job. I was running routine statistical data for an energy firm, a job I could do with half my brain. The rest of me was unoccupied. That's the reason I fell in love.

The first thing I ever cared about as far as Dascha was that she was born four days before me, almost exactly half the world away. We were like barrette girls in that way, part of the same clutch of the planet's organic matter, nourished on the same zeitgeist and political vibrations and the same matrix of airborne pollutants and from the same global stocks of rice and corn and wheat.

She was a strategic analyst. She was too unconventionally beautiful for me. Her hair was straight and cut jagged; her lipstick was dark in the daytime; she never looked anyone in the eye. I should have known that meant she had a dishonest heart, but I was falling for her by then, wracked with a curiosity that strove to devour all her facts, full up with more questions than I'd ever had for myself.

We shared a cab after an office night out celebrating a new shale gas contract, and when we pulled up in front of Dascha's house on a posh street in St John's Wood she said,

"Do you want to come up for a minute? I've just renovated my kitchen and I sort of want to show it off."

I could smell a blend of whisky and craft ale—it could have been either of us or both. There was a heat in me everywhere.

"Yes," I said.

I went up and I saw the kitchen and also the couch and also the bed. I did not think of barrette girls the whole evening, which was a miracle. I was thinking about love. I did not know I was lining myself up for a terrible wound.

There's an unlikely bedtime story about a creature. This is my second favorite bedtime story. It goes like this.

Deep, deep in the earth, right in the middle of the world, is a pit. Inside it, there's a creature. It's alive. There's no record of how it got there. There's no way for it to get out. It has been in this pit—more like the pit of a fruit than a pit in the ground—since the world began.

People drilled and drilled into the earth, and the plan was to breach only the surface, to access the good things pocketed just out of reach. People wanted good things faster than the pockets could replenish. The more people drilled, the less full the pockets were with good things.

Drills got sharper. Drilling got deeper. There were pockets deeper down, but not as many, and more expensive to reach. You'd think something like that would bring this project to a halt, would grind in its gears, but the opposite happened. People got more insistent. They set up more drills, and larger drills, and better drills.

That pit in the middle of the world? They eventually drill right into it. One person will tell you it was an accident; the measurements were wrong, they didn't know how close they were. Some people will tell you that scientists knew there was a pocket like no other down there, a seam of unadulterated fuel. A pocket the size of the moon, a pocket to last so long that greed would have to metastasize to exhaust it.

So the drills pierce the pit, and out flutter-scrabbles a creature. It's downy, colored a prismatic earthtone that's unknown to the earth's surface, and it's barely moving. The people are amazed. They call scientists in. The scientists bathe the creature in oxygen, which it cannot breathe. And when they do, the creature begins to change. Into a little girl, with a beautiful mother-of-pearl barrette in her hair.

That's the unlikely bedtime story about a creature.

I've been thinking about my death a lot. The more I think about it the more I realize that death is not a type of suffering. I think about the taxonomies of death: instantaneous oblivion, or slow death like the progression of disease, or an unraveling—I think of Patrick's hands around my neck and the dimming moment before my mother tears his leaden weight off my chest.

Andrew and I are getting the barrette girls ready for the trip to the location. Their faces are lit in the blue light of the surveillance stream projected against the living room wall. The street with the brass instruments workshop is mostly deserted under a sudden assault of freezing rain. One woman smokes a vape under the dripping awning of the off-licence on the corner. With her free hand she's rearranging sickly imported papayas in the fruit display out front.

We put a tiny coat and an orange knapsack on each barrette girl. It is hard to maneuver their indifferent limbs into clothing.

"Give me your hand, honey," says Andrew to a barrette girl. "No, no, the other hand."

"Stop inventing things," I say.

Andrew stops moving. "Are you addressing me?" he asks after a moment.

"Who else would I be addressing?"

It's very silent in the room; it's nothing like a room with a group of girls in it. I wonder on a whim if the barrette girls are entertaining thoughts about death. What is death to them? Certainly not suffering. Perhaps a state change, solids melting, liquids evaporating. They contain the coiled potential of their deaths inside, but so do we all.

After the Barthes locked me out of their house I sat a long time against the fence of a council estate, hugging my suitcase in the rain, and I thought about what I would do with my next barrette girls. It could seem an accident; there could be an iron left face down in the next room, there could be a humongous fire, there could be no survivors. But I shivered so hard—my hands and feet got so numb—that some latent survival instinct kicked in. My next barrette girls came and went, and I nourished my anger, and I made a little money, and I found a new place to live.

"Let's go," Andrew says. "It's 2:58 and they said to move at three." The recipe-following exactness of the newly initiated.

"You take these ones." I nudge eight little orange knapsacks, strapped to eight pairs of shoulders, in the direction of the door. The floorboards creak drily under the carpet. The barrette girls I lead move with straight backs. If there's a preternatural bounce in their steps, only Andrew and I will notice it.

I suppose people like Andrew always want to make the world a better place. They must have seen this in Andrew right away, fed him the type of drivel that gets to people with morals. Chemistry textbook inserts laced with fairytales: not all natural resources are created equal, and this? This is the most noble of chemicals. Weep for the MRI magnets under threat, the precision manufacturing, the particle accelerators. They rely directly on you, Andrew. Do not falter.

Then there's the spiel everyone gets, earnest people like Andrew and tattered people like me. What a strange whimsy of civilization, that molding flesh has gone so easily for us, that it's cheap and ethical, that we've learned what no one else knows—that molding flesh generates so precious a byproduct.

It would have been criminal not to optimize for this, they'll have told him. All those imaging machines, silicon wafers, physics experiments that couldn't exist otherwise. Nobody—no real person, if you think about it—gets hurt. Nobody needs to know. By the time everything is in canisters and on the way to hospitals and manufacturing plants, there's no contamination at all. Nothing to show origins. No aerosols of blood. No spinal fluid. No eyelashes hair tears.

We've been given a decoy school bus for our trip to the location. It's a rental license plate, the kind of school bus mostly reserved for hen parties and frat boys on pub crawls, but the drive's not long, and Andrew has a kind face. We load the bus. Andrew pulls us out onto the road with his kind face and his orange hat, and he's sweating a dark ring into his shirt collar, but no one out there knows it's so cold in the bus that we can almost see our breath.

"Take a left at the end of the road," I tell Andrew.

"Sunday..."

"Everything has been smooth so far. It's all we could have hoped for. Don't."

"We don't know what kind of people they might grow up to be. If we give them a chance." He whispers so that the barrette girls will not hear. Oh, Andrew. Those who better not hear have already heard.

"You're on the wrong track with this," I soothe.

"Where's your humanity? What have they done to you? I know you're not this person. These are little girls—they could grow to be people. I know you have a heart. I know it."

Andrew's driving slower, not faster, as his words speed up.

"Do you know what the hats are for?" I ask him.

"What?" He spares a glance away from the road, at me, at my orange hat. "What hats?"

I take the orange hat from my head, which is identical to the hat on his head, which is a little different to the knapsacks, and start unrolling the false lining. I expose the strip that looks like a short red adhesive plaster. A barrette girl coughs behind me. I pause, until I remember that I've heard barrette girls cough before.

"They didn't tell you about the hats," I say, and I'm not thinking about Andrew wronging me, about the danger he's put me in, about the kind of death this adhesive plaster contains. I'm thinking I'm proud that they told me about the hats but didn't tell Andrew.

I peel the red plaster the way they taught me, pinching it with my nail so that I don't touch the sticky side, and I reach over like I'm fixing Andrew's collar as he drives, and I leave the plaster behind on the skin of his neck, over his jugular.

He looks over again. "What the fuck, Sunday."

"Get out of the seat, darling," I say. "You don't feel well. Get out of the seat."

"I knew you were crazy but—" he says, mournful. Then I see his right-hand-side slacken. His rubbery hand flops into the gap between the spokes of the flat steering wheel. "Shit. Oh, shit, oh God, oh shi," he says. Too much drool gushes out of his mouth and onto his shirt, another dark stain.

"Come on, Andrew," I say. "Off you get, before you crash us into a wall."

He moves heavily, all dead weight and spasms. I take the driver's seat with a foot on the brake, then shift to the accelerator while Andrew's saying oh-shi-oh-shi in a heap in the bus aisle. I look back and some of the barrette girls are watching him. Involuntary nervous system tics: eye muscles tuned to motion in underdeveloped brains like sprouting cauliflowers.

It turns out that if you've been wronged enough times, you learn to assume it before you're sure it's coming.

"It's okay girls. Everything is ready for you. You're nearly home now. It's nearly quiet time now. Let me tell us a story."

Helium is the most bountiful element in all of outer space. So, with all that helium inside, girls, you're built to the proportions of the whole universe. Cool, right?

I can be honest here? So close to the end? I like thinking of you as little space snowglobes. I like thinking of you as bonsai galaxies. I like thinking of you as canisters of squirrely giggles. These are the things I actually like when it comes to you.

You know what you're not missing out on? Pain. Pain, awareness, intentionality—the pillars of personhood. But girls, is personhood really worth the suffering?

Pain: that poor man wallowing on the dirty bus floor. Do you want to feel what he feels? No. Be bonsai galaxies. Don't wish to be him.

At the location I unload the barrette girls in twos, like good schoolchildren. They wait for me beside the bus. Tufts of breath come at synchronized intervals. Dr Ganesh is standing on the snow-salted sidewalk in a tailored grey peacoat. He's wearing a crooked yellow bowtie.

"Andrew is in the bus and you will need to remove him." I give Dr Ganesh a hug. His slighter frame makes our embrace seem brittle and forced.

"What happened, Sunday?" he asks. He does not sound especially sad, his question evidentiary.

"He snapped. Everyone I surround myself with ends up doing something crazy." I straighten Dr Ganesh's bowtie. "You know my history with people."

I don't know how long we hold each other's stares before Dr Ganesh looks away. He begins to lead the first pair of barrette girls by the hand. Their mother-of-pearl barrettes flash in the cold light of the season.

I catch up with Dr Ganesh at the door of the location. He shows me a grimace.

"We spend a long time training up someone like Andrew. Did you try to de-escalate?"

The frosted glass diamond in the door is covered in fingerprints. "He was a danger. He thought they were real."

Dr Ganesh leads barrette girls into the location, counting them, a soft mantra (I think: trombone, saxophone, horn).

When he is done he says, "Andrew did not think they were real. They are so blatantly not real." He shoves a barrette girl on the side of her head. She corrects herself like a punch clown. "I do wonder sometimes who the danger is, Sunday."

"Dascha tried to phone me last month," I say. "She asked me if I was ready to leave this behind. She said I didn't need the money, that I have professional skills, the usual shit. Offered to pay my way if I quit."

"And what did you say?" Dr Ganesh asks.

"I told her I'm doing this because the world needs me to. And it helps to have something to focus on. A single bonfire of anger instead of the beginnings of forest fires everywhere. Did I ever tell you about my big brother Patrick?"

"Many, many times." His tone is acidic. He is the opposite of an inert entity. "We're here now, and we're a person down, so keep your musings to yourself. I need you to do twice the usual work."

I should have known Dr Ganesh was headed this way too.

It's only uncomfortable to watch the first time. I wish they had no bones and drifted to the ground like feathers. I wish I did not have to heap them at the mouth of the incinerator.

There is a sucking noise when the machine has extracted all the helium and flesh begins to vibrate in the vacuum of cavernous torsos—that part is the hardest to become accustomed to. Andrew would not have liked that part at all.

The barrette girls approach the machine and, palms up, place their barrettes on a steel platform. Why do they do this? Is it bred into them? An instinct? A taught behavior from infancy? I watch them: their eyes are on the girl ahead, they see what happens, but still they come forward without hesitation.

Each barrette is genetically keyed. The machine reads a registration number from it and loads it in a mechanical arm. When twisted against the chest, the long edge of each barrette—molded tungsten carbide, sharp as anything—extracts an exactly round disc of flesh from below the sternum. Here the barrette girls uniformly emit a sort of sigh. The used barrette is swallowed into the extraction machine and clinks deep in its belly while a rubbery ring suckers onto the hole in the chest. The mat beneath the barrette girls' shoes is a massive, absorbent surgical pad. The chemical smell of this pad is on my fingers. I avoid putting my hands on my face.

There are five barrette girls left. Five girls are more than enough. Dr Ganesh has gone to the other room to watch those of us watching the surveillance stream.

There is a tangy sweetness to this happening while Dr Ganesh exercises his distrust.

"Come this way." I corral the last barrette girls towards the front door. Outside a wet-feeling wind has picked up. I arrange the girls along the porch; if we go onto the lawn the surveillance cameras will see.

There are different taxonomies of death and there are different taxonomies of personhood. There are people like me, and there are people like Dr Ganesh Dascha Patrick Asher Barthes. There are no people like the barrette girls, but in spite of this the barrette girls can be taken apart piece by piece, like Andrew can, like Dr Ganesh can, like I can.

"This way." I lead the barrette girls to the porch's side railing and pick each one up under the arms and put her down on the ground below. Their clothes are warm and they are so, so light. Lighter full than they are empty.

The surveillance drones do not see the side of the house, but Dr Ganesh will know when he looks for me. Or when he counts the barrette girls on the heap. I let us into the storage shack beside the house. Fertilizer bags lend the space a noxious smell. There is very little room and though it is cold and tight, the girls do not know how to huddle. They stand rod still.

"Bonsai galaxies, girls. Remember that. We've made our peace."

How do I pick one? Their eyes all look at me the same way. Five is more than enough; five is too many. I only need one big brave lungful devoid of oxygen. I only need one.

I pick the one in the middle, for symmetry.

I go to my knees, put my hands out for the barrette. She removes it from her hair and holds it out to me, palms up. Reflex, not intent.

I steady the shoulder and press the sharp barrette to the solar plexus. I do not expect how easily fabric and flesh give beneath the twisting cut. The barrette girl sighs. Even with my hand shaking, I pull the disc of a body cleanly away on the barbs of the barrette and slide my palm over the hole in a torso.

There's a lot of blood this way. I'm not precise like the machine.

I regard the barrette girl I have chosen. "Dying is the only human thing you can do. Dying makes us similar."

The eyes are on me but not on me.

I lean in and replace my palm with my face and make a seal with my cheeks and chin. It's awkward. Blood slides against my jaw. Blood is a curtain. Anger is a curtain. The taste of blood in the round breach of a chest is very strong. I wait to hear any words from this barrette girl, or the others, or Dr Ganesh. But I suspect there are no words left in the world. I breathe in long and luxurious, I breathe and breathe, scentless bliss, until I fill my body with helium. I stop seeing and stop feeling. The wronging melts away.

SARA SAAB was born in Beirut, Lebanon. She now lives in North London, where she has perfected her resting London face. Her current interests are croissants and emojis thereof, amassing poetry collections, deadlifts, and coming up with a plausible reason to live on a sleeper train. Sara’s a 2015 graduate of the Clarion Writers' Workshop. You can find her on Twitter as @fortnightlysara and at fortnightlysara.com.