THE SOLACE OF COUNTED THINGS

Natalia Theodoridou

Number of kitchen tiles: 208

Drawers in the house: 12

Available wings (pairs): 3

He paces in his unlikely menagerie, counting the fanged faces lining the wood-paneled walls in endless variations of teeth—wolf, jackal, dog, wolfdog, jackalfox, doglion—the arms of an internal clock ticking away the hours from lightless dawn to lightless dusk (number of open windows in the room: 0), waiting for her to come back. There are no more animals to treat, no wood to carve, no gypsum to mould. All that is left, to count.

Heartbeats since she left this morning: 28,920

Heartbeats until she comes back: 15,600

A house in the woods, a body kept, hidden from the world, who would have thought he would end up like this, like something out of a fairy tale, only warped, as if viewed with the head tilted to the side, eyes half-closed. He takes a look around his space—sometimes he thinks of it as an atelier, most of the time he thinks of it as a time capsule, an avant-garde, demented Noah's ark: a million years from now, when humanity has become extinct, the Earth's new inhabitants will discover his corpse in this peculiar prison in the shape of a home, surrounded by the most well-preserved specimens of dozens of rare species. Human history will be rewritten backwards. Future scientists will give papers about the extraordinary chimeras that once populated earth.

He laughs out loud, the sound crooked, wrong, who laughs here, is it the deer, the bear, the two-headed fox? The laughter's all too human, but how can it be? There are no humans here.

And then, finally, she comes back, as always:

Sister. Little sister, entering the place like a hurricane, doing damage that will never be truly healed, but also bringing with her the most comforting of loot: a fox's tail, the beak of a vulture, a pair of bat's wings, lace-thin, membrane-soft. Wanting something in return, of course. Wanting everything in return.

And then asking, blood-mouthed and long-eyelashed almost as much as me (we always looked so much alike, didn't we, sister?), asking "do you like your presents, brother-sweet? Did I do well?"

And I. And I.

I hide the brokenness of my body the way one averts one's face from an onslaught of ash and sand, and I thank her. "Thank you," I say. Dear sister mine.

Number of bones in my body: 270

Number of bones, never broken: 263

She leaves again in the morning, but he stays in bed without moving, until he's certain the dust has settled and the house is quiet. Then he tiptoes around the ruins she's left behind. He makes his way to his workbench, picks up the carving tools, the dead fur, the wood wool. He closes his eyes and stuffs. Stuffs and stuffs, skin stretched, sewn closed, feathers covering the seams to perfection, and there it is, a fur-covered bird, flightless wings, eyes that gleam in the dark, still life, almost real. Almost worth it.

When Mother was alive, she absorbed little sister's rage, swallowed it whole like a cherry (pit, stem and all), leaving for me nothing but the aftershocks of her violence, her gifts of dead birds for me to skin, stuff, and mount.

Mother thought her wrath was a gift from God. "Her voice is the voice of storms," she said. And then "She speaks the language of her Father."

We each had our very own species of madness.

Antlers and horns. Blunt knives and sewing kits. Stuffing and feathers and fur. Fake eyes and snouts and wings, always wings. Words played around on the tongue like hard candy: Closure. Enclosure. Enclosed. To be enclosed.

He longs to find himself outside again, to feel the chill on his skin, his clothes moved by an unenclosed breeze. He eyes the moths gathered around the lamps in the ceiling—"Where did you come from?" he asks them. "How did you get in?"

In the time before our mother was no longer alive, before my world became incarcerated, barbed sisterly love enclosing breath, mouth, body, and light, there was a period when I would put wings on everything I made: winged rats, winged badgers, a winged, milk-mouthed fawn. My best friend at the time (at the time of friends still, outside still, still in the world of windows and doors and out, outside, still), she commented: "It's rather an obvious metaphor, darling, don't you think?" But it was not obvious to me, not yet, that early aspiration of escape, dreamt too soon, abandoned too lightly. How could I have known? How could I not?

When he realized what he had been doing, of course, the spell was broken and his work evolved: trees started sprouting from owls' heads, birds nested inside his deer, tentacles crowned his foxes. When she shut the windows tight with nails and planks and tore out the landline, when she bolted the door and brought in canned food and light bulbs with a wheelbarrow, he made an antelope with two human hands clasped over her snout. A cry postponed. A taxidermied protest, too subtle for her to register and thunder over. His hurricane sister. His sister, the storm.

Teeth: 32

His first escape she met with a new latchbolt to the door, the second with a temporary chain to his ankle and a gift of a dead rabbit, the third with a knife to the shin and a hugful of ferrets. He no longer tries to escape.

Number of eyelashes, left eye: 250

Number of eyelashes, right eye: 225

Hairs on my head: 1232 (until I lost count)

It is morning and he's waiting for the dust to settle before making his body leave the bed. He hears animal cries. There is the hesitant neigh of the horsedeer, the pitiful sigh of the winged salmon, the anxious croak of the crow-tailed goat. Instead of getting out of bed, he covers his head with the blanket and counts his breaths. When he reaches a hundred, he holds his breath and makes himself go to his workbench. He opens the jar of dead moths and spills them out, a swarm of wasted flight. He kneels over them and starts plucking their wings one by one, with the tender attention of someone tending to a beloved's wounds. When he's done, there's a small pile of fuzzy flightlessness on the floor in front of him.

Then, he makes a human torso out of plaster and gypsum gauze. "Sister," he calls it, and then he starts sewing the moth wings together, to make the most delicate shirt. He pricks his fingertips all the time.

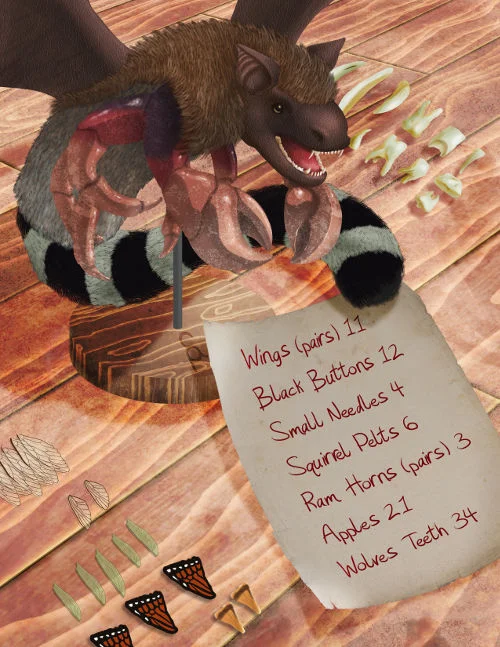

Then, his sister comes back. He wants to ask her for a new set of needles—he needs finer ones for such delicate work, maybe a couple of buttons and glue. He's written everything down, made a list, but as soon as he says "Could you bring me—" she knocks the air out of his lungs, that earthquake of a sister. Her force enters him, squeezing out all of his thoughts through his mouth—he blocks out the pain by focusing on the painted ceiling, a naked tree dividing the wooden sky into rhizomatic parts, until she retreats, sad as rain, sad as a natural disaster, sorry. Sorry for what, he wonders. She never says what she's sorry for.

Like a boy from a folk story, a fairytale brother, he vows not to speak again until the shirt is complete.

Hard, bitter candy on the tongue again, words stinging like a canker sore, a verbal wound. Count. Countable. Uncountable.

Teeth: 30

His sister doesn't come back the following night, nor the night after that. Time passes and his sculpture is almost complete, the wing-spangled mothsister, armless, unarmed, for once. The third night of her no-return, he dreams rogue taxidermic dreams, sees himself skinned, stuffed and mounted, a one-of-a-kind curiosity, the shark-headed sculptor, his mouth overflowing with teeth.

She comes back the fourth night, overcast and dark. She hands him the glue, the new sewing kit, the buttons he wanted, and then she hands him the list with all of the items crossed out with clean, careful lines, and when he says "Thank you, sister," she turns into a storm again, the angriest yet.

Is this the wrath of God, he wonders as he watches her destroy the chimera, the horsedeer and the wolfdog, the crowed tree and the wise fish. He expects the animals to cry out again, but they don't—they remain mute, silent. In the end, she tears the mothshirt off the sculpted torso and shreds it to pieces. "Not Sister," he shouts, and then clasps his hands over his mouth, shutting in the words and taking cover, preparing for her thunder. But she doesn't thunder. She licks her dust-covered fingers clean and then she turns around and leaves, bolting the door behind her.

He counts the wreckage of her kingdom, finds it lacking and broken, but only half-heartedly so. He finds spared wings, antlers moved mindfully to the side, dead sparrows preserved whole and precious, carefully taken out of the way when he was looking elsewhere, mesmerized by her loudness.

Sister. Not the wrath of God then, only an anger imitated, never your own, never fully your own, only borrowed, long-ago, father-shaped. Mother bat-blind, big brother a coward, content in the leftovers of your despair. Too late for love-knitted shirts to turn us back now, sister, sweet sister mine.

She doesn't come back for weeks. She's left him water, but no food other than a couple of tin cans and a bag of slowly rotting apples. He spends the days reassembling what he can of his beastly ecosystem, and the nights counting his fingers, his knuckles, his cheekbones, his ribs in the pale light of the moth-covered lamp. He passes his tongue over the hollow spaces in his mouth, and finds them filled.

Teeth: 35

She doesn't come back, doesn't come back, and his body is left unclaimed, unseen, unshadowed in the sun-starved house in the woods. Is that all, he thinks, is that how it ends, sister, sister, sister-sweet, I am ready then, come on, but as the flesh wastes, the bones multiply, and as he counts and recounts the fingers, the knuckles, the ribs, he finds himself to be more every time.

Teeth: 42

And then the water runs out and the light bulb fails and so he sits in the dark and waits for her to come back, with her loud thunder, her dead gifts, her sister-touch. "Sistersistersister" he spells into the empty, still air and he counts himself and he sharpens his eyes, his nails, his teeth, because one day, one day she has to come back and then he'll be truly ready, no longer a coward, but all teeth, transformed all the way at last, and ready as nails, and ready as teeth, a true match for her gifts. His sister's brother for the very first time.

NATALIA THEODORIDOU is a media & cultural studies scholar, the dramaturge of Adrift Performance Makers (@AdriftPM), and a writer of strange stories. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Clarkesworld, Apex, Shimmer, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and elsewhere. Find out more at her website, or follow @natalia_theodor on Twitter.